Some Things Students with Disabilities Want Their Teachers to Know

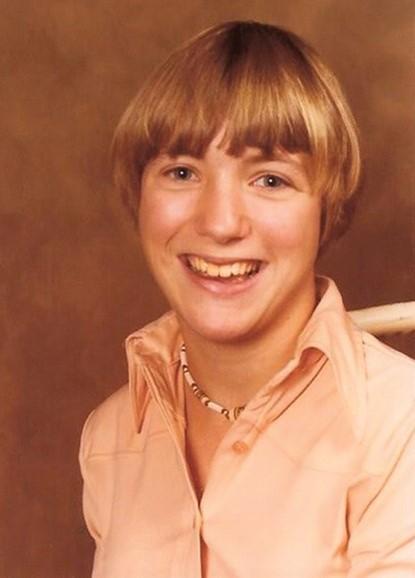

My high school adventure began in 1976, and I wanted my teachers to understand two things:

- I expected my teachers to have the same high expectations I had of myself.

- I was just an ordinary teenager. I wanted to go to prom, loved football, and had a major crush on John Patterson for most of high school.

Being one of two students with disabilities at Somersworth High School back then was a huge challenge. For the first few weeks, every time my teachers interacted with me, I could see and feel their anxiety. I guess that’s why I started making jokes all the time: to help them relax. My two brothers and my sister were in high school at the same time, and I had many friends from elementary and junior high. They would tell teachers that “it’s just Kathy,” which made it easier for them to treat me like any other student.

My ultimate goal was to graduate from college with a BA in elementary education. The guidance counselor told me that kids with disabilities did not go to college. I desperately wanted to prove him wrong, and I did.

Fast-forward to today and this article. The school year is about to start, so I thought it would be interesting to ask students with disabilities what they want teachers to know.

Tameka is 10 years old and loves art and soccer. She has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). She is a little worried, “I am excited about starting middle school, and I'm looking forward to making new friends, but I hope my new teachers will help me deal with bullying if it happens.”

Three in five kids with disabilities are bullied compared to one in five kids without disabilities. By age seven, 12% of kids with disabilities report being bullied. When a bully targets a student based on their race, color, religion, sex, disability, or national origin, it can be considered harassment, according to both the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) and the Department of Justice (DOJ). Federally funded schools are required by law to address and resolve all matters involving harassment.

I met Tyler at the 2024 Kids Chronic Health Awareness Awards. He was wearing a shirt that read, ‘I’m wicked smart.’ I loved it. Tyler is a 14-year-old incoming freshman at Merrimack High School. Like many teenagers, he loves the Red Sox, walking the family dog, Emma, and playing video games (especially golf). He also has Cerebral Palsy. His communication style includes a combination of words, personalized sign language, and an application on his iPad to assist with speech.

When I met with Tyler, we spent the first 30 minutes getting to know each other to help Tyler relax. I needed to learn more about his communication style, and he needed to get comfortable communicating with me (over Zoom, nonetheless). Tyler’s mom, Karin, explained that Tyler was not enrolled in any general ed classes at Merrimack High School. The staff was unsure about Tyler's ability to participate because communication was difficult, and Tyler was easily frustrated. With a lot of effort and courage, he repeated the word ‘nervous’ over and over in combination with touching his voice box. His mom helped me understand what he meant; she said,

“I think he is worried about using his voice and not being understood in class.”

She then asked Tyler if this was why he didn’t talk in class. He smiled and nodded his head yes.

I explained to Tyler that it may not always seem fair that people with disabilities have to work harder to prove their intelligence. How else would he show how wicked smart he was if he didn’t keep trying to communicate?

Riley is a 12-year-old seventh grader. He likes science, especially chemistry and math. “I like science a lot because I want to figure out how the world ticks,” he said. I joked with him, “Do you like chemistry because you like blowing things up?” He laughed. “No…well maybe a little.”

He says he’s nervous about school because this is the first year he’ll be home-schooled. When I asked him about the reasons he is going to be home-schooled, he said, “I have autism, I’m not very social, and I get frustrated easily.” I asked, “Does this mean your mom will be your teacher?” He responded yes, but his mom added that he will attend VLACS (an online Virtual Learning Academy Charter School). He said,

“It will be new, so I’m a little nervous. I hope my teachers are patient with me.”

I was impressed with how self-aware and honest the students were with me. A new school year can bring new challenges for all students. Disabled students face additional challenges, which are often more personal; for example, they can be about things that they cannot control, like their voice.

From Where I Sit

Dr. Seuss once said, “Why fit in when you were born to stand out?” School years are often marked by a struggle to fit in and find our place and our people. It would be great if our talents and skills were recognized regardless of disability. I envision a world where disability is seen as another form of diversity. I just hope it happens in my lifetime.

Teachers have a big job—especially for students with disabilities. They need to keep the lines of communication open and listen carefully. They are often the ones who can help students make connections and find community. Teachers can also encourage the development of talents and skills that may not be as easily recognized as those of their non-disabled peers. I want teachers to remember that students with disabilities face extra challenges, but they also want to be treated like everyone else.