Jennifer McLaren, MD

Assessment

The core features of Bipolar Disorder are manic or hypomanic episodes, depressive episodes, and a marked change from an individual’s baseline. The severity of an individual’s intellectual disability will influence the presentation of symptoms for Bipolar Disorder. Individuals with mild to moderate intellectual disability may report their internal feelings and observations of their own behavior. Individuals with a more significant intellectual impairment may not be able to verbalize their feelings and observations. For all individuals, observation of overall presentation and vegetative function along with collateral information are key. The prevalence of Bipolar Disorder is lower than anxiety and depressive disorders in this population and requires clear knowledge of the presentation is required in order to prescribe effectively.

The diagnosis of Bipolar and Related Disorders requires meeting current diagnostic criteria for one of the following: Bipolar I Disorder, Bipolar II Disorder, Cyclothymic Disorder, Substance/Medication-Induced Bipolar and Related Disorder, Other Specified and Unspecified Bipolar and Related Disorders, and Bipolar and Related Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition.

Case Vignette

Nancy is a 23-year-old female with mild Intellectual Disability. She had a chaotic childhood. Her parents experienced significant mental health issues, and Nancy also had multiple psychiatric hospitalizations though these records are not available. She currently lives in a family setting with a married couple and their adult daughter.

The family notes that Nancy has both very dark periods and happier times that are distinct changes from her baseline. The caregiver describes episodes where Nancy sleeps only a couple of hours per night, becomes very bossy, and believes she is the director of her day program. During these times, her speech is louder and quicker. She seems to jump from topic to topic and activity to activity. She is up all night arranging and re-arranging her room. These episodes last for 2 weeks at a time and then Nancy crashes into sadness.

During times of sadness, Nancy sleeps more and will not get out of bed. She appears irritable, withdrawn, has low energy and nothing seems to give her pleasure.

Nancy begins Lithium and it is titrated to a therapeutic blood level. She does well for six months then begins to frequently miss her Lithium as she does not like how she feels on it. She experiences another manic episode and during this episode, she begins planning her wedding even though she is not in a relationship. Her caregiver can also hear her talking to herself loudly in her room and at the dinner table. This is different than Nancy’s typical self-talk as she appears to be distressed and notes she would like the voices to go away. Nancy is started on quetiapine with resolution of manic and psychotic symptoms. She also did not experience a depressive episode. Nancy continues to take her quetiapine regularly at a follow-up appointment and by all reports (Nancy and her family caregivers) she is doing better.

Case Summary

This vignette highlights several important points:

- Potential family history of Bipolar Disorder

- Grandiosity in someone with ID or ASD may be exaggerated claims of skills or accomplishments.

- Individuals may have difficulty adhering to treatment for many reasons. One reason may be medication side effects. Include the patient and supporters in discussions and decision making.

- Auditory hallucinations are intrusive and distressing. They look different from an individual’s baseline self-talk.

- When choosing a medication, you may consider one that will treat as many symptoms as possible to avoid polypharmacy (e.g., quetiapine to target acute mania, depression and psychotic symptoms)

Key Components in Assessing Bipolar and Related Disorders in Individuals with ID and ASD

Comprehensive history with collateral information, including behavioral observations from caregivers, residential staff, day staff, etc.

- Good understanding of individual’s baseline functioning and change from baseline.

- What does the individual look like when they are doing well?

- When did they last appear that way?

- Symptoms of mania or hypomania include a persistently elevated, expansive or irritable mood with the following symptoms

- Mania: symptoms lasting at least 1 week and causes functional impairment

- Hypomania: lasting 4 consecutive days

- 3 or more of the following symptoms or 4 or more if the mood is irritable

- 2 or more if limited expressive language skills or 3 or more if mood is irritable

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep

- More talkative or pressure to keep talking

- Flight of ideas or racing thoughts

- Distractibility

- Increase in goal directed activity

- Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities

- Timeline and Severity

- When did the patient begin having symptoms?

- On a scale of 0-10, how severe are the symptoms with 10 being the worst?

- Previous episodes of mania and depression and response to treatment

- Assess for psychosocial stressors and abuse

- Comorbid substance use/abuse/dependence

- Family history of mental health issues and suicide attempts or completions

Physical examination: Assess for illnesses that can be associated with Bipolar Disorder (e.g., Hyperthyroidism, Lupus, Epilepsy, Stroke)

Review individual’s medication list. Assess if medications are causing/contributing to mania/hypomania.

- Ask about complementary and alternative medications.

- Some classes of medication can cause mania (e.g., corticosteroids, antidepressants, stimulants, baclofen, bromide, bromocriptine, captopril, cimetidine, cyclosporine, disulfiram, hydralazine, isoniazid, levodopa, metrizamide, procarbazine, procyclidine)

Mental Status Examination: Assess suicidality and homicidality, psychotic symptoms, catatonic symptoms, and future orientation.

Labs to consider: Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), complete blood count (CBC), liver function tests (LFTs), renal function tests, and urine drug screen

There is a lack of research on psychopharmacologic treatments for individuals with Bipolar Disorder and IDD. The psychotropic medications to treat Bipolar Disorder in typically developing individuals are utilized for individuals with IDD.

Treatment of Mania

It is important to provide psychoeducation about the chronicity and course of Bipolar Disorder, treatment, and the importance of adherence to treatment. Manic and hypomanic episodes are treated with the same psychotropic medication. A variety of medication shows comparable efficacy in treating mania and are considered first line medications including lithium, quetiapine, divalproex, asenapine, aripiprazole, paliperidone, risperidone and cariprazine. Among these medications, lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, risperidone and quetiapine have a favorable safety and tolerability profile and a stronger evidence base in patients with ID and ASD. These medications should be considered first to treat mania in individuals with ID and ASD.

Which medication to choose?

The choice between lithium and valproate, and the choice of the antipsychotic should be based upon the following:

- Individual’s past response to medications

- Past response to medications of family members with Bipolar Disorder

- Symptoms

- Comorbid general medical illnesses

- If patient has epilepsy and is treated with valproate for their epilepsy, then optimize the dose of valproate to treat mania. Valproate’s therapeutic blood level for epilepsy is lower than for mania.

- Liver disease: avoid valproate

- Renal disease: avoid lithium

- Obesity: avoid olanzapine

- Drug-drug interactions

- Patient preference

- Cost

Response to anti-manic agents is typically seen in 1-2 weeks. If manic symptoms are not controlled, then consider dosing optimization and medication adherence. If the response to medications remains suboptimal once these factors are optimized, then a re-evaluation of the diagnosis should be considered. If the diagnosis of mania remains consistent and an individual does not respond to a first line agent, substitute a different first line agent before preceding to second line agents. The second line agents include olanzapine, carbamazepine, haloperidol, lithium plus valproate, olanzapine plus valproate or lithium, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Figure 1 illustrates an algorithm for treatment of mild to moderate mania in individuals with IDD.

Treatment of Depression

Consider Positive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to help the individual learn coping strategies to manage depression. First line psychotropic medications to treat depression in Bipolar Disorder include the following: quetiapine, lithium, lamictal, lurasidone, or lurasidone with lithium or divalproex. Second line agents include the following: Divalproex, SSRI or bupropion, ECT, cariprazine, and olanzapine-fluoxetine. Maintenance treatment is important in Bipolar Disorder to prevent future episodes of mania and depression.

Figure 1. Consensus treatment psychotropic algorithm – Manic Episode Mild-Moderate Severity

* Step 1 agents: lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, risperidone, and quetiapine

^Combination treatment if symptoms becoming more severe: lithium or valproate plus quetiapine, aripiprazole or risperidone

#Second line agents: olanzapine, carbamazepine, ziprasidone, haloperidol, lithium plus valproate, olanzapine plus valproate or lithium, and ECT

Severe Mania

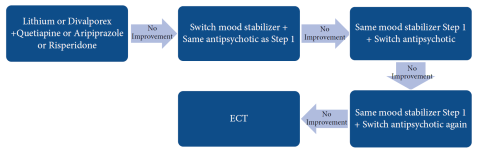

For patients with severe mania, consider initial treatment with lithium plus an antipsychotic or valproate plus an antipsychotic (4, 5, 12-14). A severe manic episode that does not respond to one medication combination should be treated with a second medication combination such as switching the mood stabilizer: lithium to valproate or vice versa (4, 5). If the individual fails to respond after 1-3 weeks of treatment then switch the antipsychotic to another antipsychotic (4, 5). After 1-3 weeks if no response then switch to a different antipsychotic or try ECT (4, 5, 15). ECT should only be utilized when symptoms are severe, refractory to medication treatment or due to intolerable side effects from medications (16). Figure 2 illustrates an algorithm for treatment of severe mania in individuals with ID or ASD.

Figure 2. Consensus treatment psychotropic algorithm – Severe Manic Episode

References

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Deb S, Chaplin R, Sohanpal S, Unwin G, Soni R, Lenotre L. The effectiveness of mood stabilizers and antiepileptic medication for the management of behaviour problems in adults with intellectual disability: A systematic review. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2008; 52(2):107-113.

Deb S, Farmah BK, Arshad E, Deb T, Roy M, & Unwin GL. The effectiveness of aripiprazole in the management of problem behaviour in people with intellectual disabilities, developmental disabilities and/or autistic spectrum disorder–a systematic review. Res Dev Disabil. 2014; 35(3):711-725.

Fitzpatrick SE, Srivorakiat L, Wink LK, Pedapati EV, & Erickson CA. Aggression in autism spectrum disorder: presentation and treatment options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016; 12:1525-1538.

Fletcher RJ, Barnhill J, Cooper S-A (Eds). Diagnostic Manual-Intellectual Disability 2: A Textbook of Diagnosis of Mental Disorders in Persons with Intellectual Disability. Kingston, NY: NADD Press; 2017.

Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharm. 2016; 30(6):495-553.

Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, Bowden C, Licht RW, Azorin JM, WFSBP Task Force on Bipolar Affective Disorders. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: Acute and long-term treatment of mixed states in bipolar disorder. World J Bio Psychiatry, 2018; 19(1):2-58.

Ji NY, Findling RL. Pharmacotherapy for mental health problems in people with intellectual disability. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016; 29(2):103-125.

Malhi GS, Gessler D, Outhred T. The use of lithium for the treatment of bipolar disorder: recommendations from clinical practice guidelines. J Affect Disorders. 2017; 217:266-280.

Maneeton N, Maneeton B, Putthisri S, et al. Risperidone for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018; 14:1811.

Muir W: The use of ECT in people with learning disability. In Scott AIF (ed). The ECT Handbook (Second Edition). Gaskell. 2005.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar Disorder: The NICE Guideline on the Assessment and Management of Bipolar Disorder in Adults, Children and Young People in Primary and Secondary Care. London: The British Psychological Society and Royal Collect of Psychiatrists; 2014.

Perugi G, Medda P, Toni C, et al. The role of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in bipolar disorder: effectiveness in 522 patients with bipolar depression, mixed-state, mania and catatonic features. Curr Neuropharm. 2017; 15(3):359-371.

Scherk H, Pajonk FG, Leucht S. Second-generation antipsychotic agents in the treatment of acute mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007; 64(4):442-455.

Williamson E, Sathe NA, Andrews JC, et al. Medical Therapies for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder—An Update. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017.

Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018; 20(2):97-170.